The Archaeological Structures

Elegant and refined, the smallest of the three theatres of ancient Rome was built in 13 BC by the Proconsul of Africa, Lucius Cornelius Balbus, a Spaniard from Cádiz, using riches garnered from his victorious campaigns in Libya. Alongside the theatre was a vast, rather narrow colonnaded courtyard, referred to as the crypt. It was here that the spectators found shelter from the rain or gathered during breaks in performances, and it is on this very site that, two thousand years later, in those same structures, the Museum has been created.

In the portico, on the side opposite the theatre, there is an exedra, a vast semicircular space that can be visited today, its interior adorned with statues. The passage of time has modified, little by little, the landscape of the theatre, the crypt, the exedra and the entire surrounding neighbourhood. Over the course of its history, the complex has seen a continuous and inexorable transformation. The splendour of the Roman monument, and the dwellings and the workshops that spread out immediately around it, gave way to neglect, abandonment and destruction. This is illustrated by the various fates of the exedra, which was occupied in the 6th century by a series of tombs, used as a dump for materials produced by a nearby workshop in the following century and then chosen in the 8th century as the site of a lime kiln. Over the 11th century, the exedra also housed a balneum, a private bath complex catering to the personal hygiene needs of the monks in a nearby monastery. New dwellings were constructed against the wall of the Crypta Balbi, and these were occupied by the emerging merchants and their shops. The presence of their workshops is recalled in the name of the modern street, the Via delle Botteghe Oscure (the street of the dark workshops). In the 9th century, the Church of Santa Maria Domine Rose was built at the centre of what was the portico of the Roman theatre. This was then transformed in the 16th century into the church and convent dedicated to Saint Catherine of Alexandria (Santa Caterina dei Funari). The ‘funari’, or ropemakers, long established in this area, were particularly devoted to the saint. The convent dedicated to Saint Catherine took in the ‘lost virgins’ (zitelle), the young daughters of Roman prostitutes rescued from the streets and initiated into convent life or marriage. The girls were taught to read, write and perform certain domestic tasks. The convent survived until the modern age, while the area surrounding the Crypta Balbi city block underwent significant urban development (first demolition to open the way for the Corso Vittorio Emanuele and the Via Arenula, and then extension to the Via delle Botteghe Oscure). At the beginning of the 1940s, the city block where Crypta Balbi is located, with the convent of Saint Catherine, became the property of the National Institute for Foreign Exchange, which planned to build its new headquarters on the site, a plan that was never implemented. The area around the ancient demolished convent fell into a state of abandonment, while the surrounding houses continued to be inhabited until the 1960s, when archaeological research identified the Balbo complex as the still visible remains of the ancient monument. Some years passed before the entire block was acquired by the Italian Government, launching the extraordinary project to recover an entire area in the historical centre of Rome. The project was completed in 2000 with the inauguration of the new site of the National Roman Museum.

Portico

Precious artefacts from the imposing travertine and volcanic tuff wall of the Crypta Balbi still remain in the Museum, where one of the stucco-covered brick pillars has also been recreated. One particularly remarkable feature is the remains of the exedra, used from the time of Hadrian as a large latrine for the theatre.

The Porticus Minucia

In the area currently situated between Via delle Botteghe Oscure and Corso Vittorio Emanuele, immediately to the north of the Crypta Balbi, the 1st century AD saw the construction of the Porticus Minucia Frumentaria, a vast colonnaded quadriporticus intended for the free distribution of wheat to the citizens of Rome.

The Ancient Quarter

Between the 1st and the 5th-6th centuries AD, a residential quarter developed to the east of the exedra. Among its alleyways emerged richly decorated two-storey buildings, a bakery, a Mithraeum (a place of worship dedicated to the god Mithras) and a workshop for staining and colouring fabrics (fullery). An exploration of this quarter provides a visit to the past and a living experience of the noise and bustle of a vibrant, industrious Roman-era neighbourhood.

The Lime Kiln and Manufacturing Activities

The extraordinary materials in the exedra site confirm the role that Rome continued to play in the manufacture of luxury items in the 6th and 7th centuries. The exedra was also the site where a lime kiln was installed in the 8th-9th centuries. This was used to transform the prized marbles recovered from the nearby Roman monuments and the exedra itself into limestone. The fragments of marble originating from the excavations can still be viewed in the Museum.

The Balneum

A modest structure for the personal care of the monks from the nearby monastery, equipped with two rooms heated by floors suspended on pilasters and an oven for heating water, occupied the area of the exedra from the 11th to the 14th century. This is a unique and exceptional find, which allows us to understand how the Roman tradition of baths and body care continued without interruption until the full Middle Ages despite changes in methods and scale.

The Church

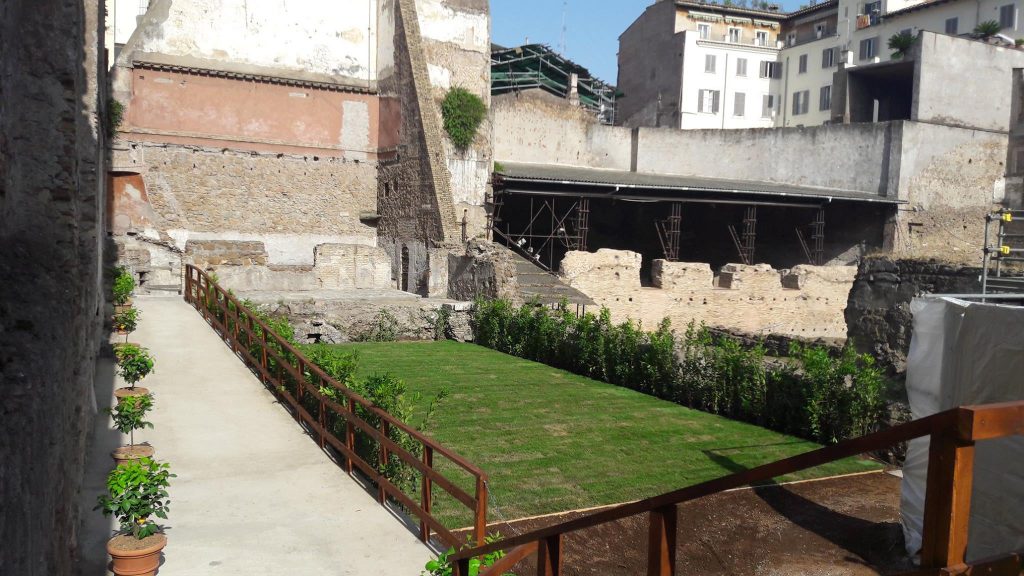

In the 9th century, the Church of Santa Maria Domine Rose was built in the centre of the portico of the theatre. This church was named for a noblewoman remembered as its founder. The church was connected to the Castellum Aureum (Golden Fort), a fortified residence erected on the ruins of the theatre. The only remaining elements of the original building are some walls restored several times prior to the 17th century. The surviving paintings show the tombs of the two bishops who were its benefactors: Ludovico Torres and Bartolomeo Piperis. These can still be seen in the Museum’s external courtyard.

The Santa Caterina dei Funari Complex

The Santa Caterina dei Funari complex was constructed in the wake of the substantial activities undertaken by the Jesuits at the initiative of Ignatius of Loyola. Made up of the church, the convent and the school for the zitelle, the complex also included a drying room and a laundry. The laundry is equipped with various tubs for soaking and rinsing laundry, visible in the exterior area, and represents a well-preserved specimen of a now forgotten work activity.